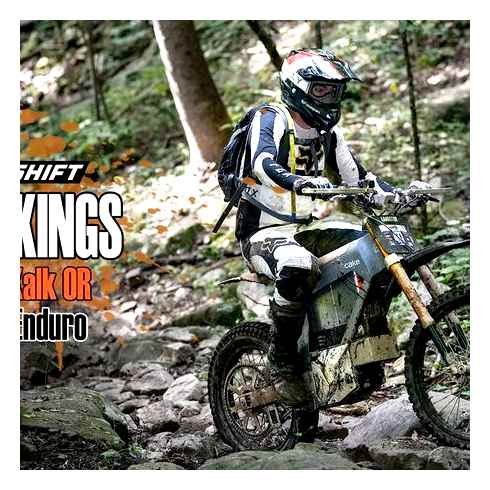

Cake Kalk OR

Supporters of e-mobility as a means of reducing carbon emissions and mitigating climate change ned to remind themselves that battery-electric vehicles are only zero-emissions machinery at the point of use. The extraction, refinement, fabrication and assembly of essentially all parts throughout an EV can still produce enormous quantities of harmful emissions, and exactly how much CO2 or other gases are emitted per process or component remains a mystery to the overwhelming majority of EV companies.

Swedish two-wheeler manufacturer Cake is attracting attention for taking a lead against that, by aiming to produce the world’s first electric bike to produce zero emissions from its material extraction ‘from cradle to gate’ – that is, from the moment it starts being produced to the moment it exits the factory – a project it calls The Cleanest Dirt Bike Ever.

Although Cake already designs and manufactures numerous models of EV, the focal point and test subject for this truly zero-emissions ambition is the Kalk, a battery-electric dirt bike that comes in off-road as well as street-legal variants. For the most part, this article will FOCUS on the off-road version, the Kalk OR.

The bike has a top speed of 90 kph and a peak torque of 280 Nm at the wheel, with power coming from a centrally mounted motor via a chain transmission with a 12:80 reduction. Its lithium-ion battery carries 2.6 kWh (or 50 Ah) of energy, discharges at a nominal voltage of 51.8 V DC up to a peak of 58.5 V, and sits within a frame made almost entirely from aluminium.

Inside the frame is the battery pack, inverter, motor and controller. Ahead of those are the handlebars, rider display, forward lights and an upside-down air fork suspension, specially designed for Cake by Ohlins, with 38 mm stanchion tubes, three-stage air springs and 204 mm of travel. On top of the frame is the vinyl seat, and behind the frame is a swing-arm that is attached to the rear wheel, with a 205 mm Ohlins TTX22 Shock integrating internal parts and springs from Cake.

Although the lifespan of the Kalk is still being defined in hours, kilometres and battery cycles, the company points to Sinje Gottwald, motorcycle adventurer and Cake B2B account manager who recently completed a 124-day, 13,000 km journey on a Kalk bike, as evidence of its real-world capabilities. Notably, it was a solo, unassisted journey from Spain to South Africa, and showed that the bike could survive travelling through some of the world’s hottest and dustiest environments.

Electrifying an off-road dirt bike represents a challenge from an environmental and shock-proofing perspective, but it makes sense for more reasons than just reducing emissions. “For instance, dirt bike applications such as motocross or wilderness exploration require a lot of torque and acceleration, and electric motors naturally have sharp torque and acceleration from stationary, along with almost instantaneous power delivery compared with two and four-stroke engines,” explains Avinash Kumar, Cake’s specialist for LCA (life cycle assessment) standardised according to ISO 14040: 2006 and ISO 14044: 2006.

“On top of that, the greater efficiency of electric powertrains versus IC-engined powertrains means you get more power to the wheel with fewer losses, and the much reduced noise compared to the typically very noisy conventional dirt bikes means less disturbance to other wilderness trekkers, less noise pollution in nature, and our street-legal models don’t bother people in towns and cities.

“It is a challenging balance to strike, however, since a bigger motor gets you more power but also more bulk and weight in the frame; it’s a similar trade-off for battery energy. Overall though, our team has worked to reach a sweet spot that balances the different performance and physical goals that are key to the riding experience, while also making our job of carbon reduction achievable.”

Central to this balance has been a FOCUS on lightweight construction in order to meet the bike’s performance targets, as well as using as small a number of battery cells as achievable to lighten the bike even more.

Company history

After Cake’s founding in 2016 by CEO Stefan Ytterborn and his sons, the first commercial delivery of 50 hand-made Kalk bikes followed in summer 2018, with series production of the Kalk starting in late spring 2019. Although the development period was short, considerable rd was fitted into this time, and more has followed during the company’s continual efforts to fine-tune their vehicle models.

“Most of our componentry was engineered, designed and tooled from scratch, the only standard parts being foot pegs, brake levers, rubber handles and the rear shock,” says Ytterborn. “Even the tyres were specifically developed to minimise the physical footprint while riding trails.”

“It might sound a bit of a cliche, like a corporate mantra, but we really do nurture our three big goals equally seriously in the course of our engineering: that’s the industrial-looking design aesthetic, the performance of the dirt bike mechanically and electrically, and the sustainability of it and all its parts and development processes from conception to recycling,” explains Krister Thour, CTO of Cake.

Much of the pre-production research from 2015 to 2017 consisted of test-riding existing and commercially available dirt bikes and motorbikes to identify what qualities (if any) were desirable in each one, in order to cherry-pick the positive aspects of the aesthetics and performance that would be targeted later in the Kalk’s development.

Some experiences during this time heavily influenced Cake to start with a blank sheet for the first concept designs of the Kalk. Ytterborn and his collaborators were for instance strongly motivated not to follow in the path of companies that had electrified existing IC-engined motorbike chassis, as they’d found such EVs to be grievously sub-optimal in many ways. These included poor use of internal space for subsystems, incorrect centres of gravity and weight distributions, and vibrations and resonances of mechanical and electrical components.

“Even some well-known motorcycle OEMs had gone down the electric conversion route, and Ytterborn found a great many respected reviewers across social media echoing his concerns that electrified IC-engined bikes just felt weird, uncomfortable and wrong, so we started with two wheels and two handlebars, but everything in between had to be reinvented at some level,” Thour says.

Building the first prototype took less than 6 months, thanks partly to the EV’s small size, but more so towards the clear agreements that the team reached over the design, materials choices, assembly processes and all other factors of production before beginning to lay out components in the workshop. There were therefore no unanswered questions that could hinder the dirt bike’s assembly, or cause misuse of what was then still very little funding and a company of fewer than 10 people.

When it came to specifying the electric drivetrain during the course of product development, there was very little in terms of pre-existing industry standards for Cake’s engineers to draw on, even in verifying the durability and ruggedness of parts against the conditions the bike would have to endure.

“There were some UN directives for transport, and a little on shock testing, but that didn’t really go any further than rudimentary safety guidelines,” Thour notes. “So a huge amount of trial and error was needed to test, iterate and validate our design.

“For instance, we have a docking connector at the bottom of the battery, so you push the battery down from above and it connects to the drivetrain. In order to find the correct connector, and make sure we got the guiding pins and required contact pressure exactly right for the dirt bike to work consistently in customers’ hands, we had to do so many physical acts of testing the bike and its parts.”

Beyond workshop and bench tests, many hours were spent at motocross tracks, on streets viable for testing, and on dynamometers belonging to local motocross garages, to validate and tune them in ideal settings, sub-optimal settings and industry-standard conditions respectively.

The Cleanest Dirt Bike Ever

At the time of writing, making the Kalk the world’s cleanest dirt bike was a work in progress, but Cake has completed some critical steps towards it.

These began in 2021, when Cake and its primary partner on the project, Swedish renewable energy company (and one of the largest energy companies in Sweden and Europe) Vattenfall first started discussing mutual interests that would eventually come together as The Cleanest Dirt Bike Ever project. Soon after, they selected the Kalk to be the model for the project, although the public announcement of the plans came in June 2021, and initial research started in September that year.

“In January 2022, we started calculating the exact amount of CO2 emissions created by manufacturing one Kalk bike, down to the very materials for each part,” recounts Isabella Pehrsson, sustainability manager at Cake and leader of the project.

“That was a tactile exercise as much as a mathematical one, in which we first took apart a complete Kalk and laid out every part flat across a workshop floor, to feel out the scope of the challenge and divide up the calculation tasks for inventory analysis and environmental impact assessments based on subsystem and material categories. By spring 2022, we had an official number.

“What was helpful was that we’d already aimed to save weight, emissions and recycling burden wherever possible by reducing material usage when the Kalk was first designed. We’ve also designed our dirt bikes the be as modular as possible, because that enables us to swap new parts in and out as cleaner or more efficient alternatives are developed.

“We’ve found that the biggest cause of emissions across the different production stages of the Kalk’s parts – and one of the most straightforward to resolve – is the absence of green energy powering the machines producing the Kalk.”

Vattenfall has been Cake’s foremost partner in the project, partly owing to its FOCUS on decarbonising industry and hence the compatibility of the two companies’ goals. As Jacques Pellis, industry partnerships at Vattenfall Communications, Комментарии и мнения владельцев, “Decarbonising the energy supply is a first prerequisite for The Cleanest Dirt Bike Ever. However, electricity is not only a power source, it is also source of innovation, both directly and indirectly through fossil-free hydrogen, which can be used as a feedstock and energy for industrial processes in order to decarbonise the production of for example steel, cement, ammonia and chemicals such as plastics or glue.

“While research has already shown that a fossil-free industry is possible, both technically and economically, this project will show real results that will hopefully inspire more industries to decarbonise.”

Kumar emphasises however that the process of calculating the Kalk’s CO2 emissions during production was very complex. Although the LCA standards specify frameworks and methodologies for breaking down parts and identifying how to calculate required CO2 emissions, lengthy discussions with suppliers were needed to uncover every CO2-generating stage of every production process and method used for every material, along with shipping methods.

These could then be modelled in standardised LCA software to output raw figures for CO2 emissions, which then had to be validated by checking against further real-world consultations and data, and gaining assurance that any assumptions made regarding data averages, aggregates and regressions made sense.

“The kind of LCA databases we use, like ecoinvent or GaBi, have different emissions figures associated with materials extraction and processing, production processes, and energy emission factors,” says Kumar. That has allowed us to cross-reference all the figures that were being put out and to compare those contrasting emissions values, to gauge how much we could trust the estimates of CO2 outputs we were getting, until we came up with a figure that we were sure was an accurate reflection of the Kalk’s emissions from cradle to gate.”

Calculating that figure has shown the scale of the challenge being undertaken by investigating and compiling the exact amount of CO2 emitted in the bike’s manufacture, and percentages for how much CO2 is emitted per component.

Specifically, 1186 kg of CO2 are generated throughout production of the bike and all its parts. For reference, Cake notes that around 25-30 t of CO2 is produced in the course of manufacturing an average electric car, and consuming a standard 60 litre tank of gasoline emits 182 kg.

The drivetrain occupies the lion’s share of this – collectively, the e-motor, battery, main controller, suspension and brakes comprise 57%, or around 676 kg of CO2, while the aluminium in the frame represents 24%, the non-drivetrain electronics contribute 7%, steel parts 4%, plastic components 3% and rubber 1%. From these figures, Cake is about to begin shrinking that amount by targeting different sources of emissions one by one, as zero-carbon options for electric dirt bike parts become available, either from outside suppliers or Cake’s other partners.

Building an Electric Business Model from Scratch

In the electrified dirt bike world today there are two schools of thought. The first has a manufacturer taking a traditional off-road motorcycle and replacing the gas-fueled powertrain with an electric one. Austria’s KTM does this, and so does a San Francisco upstart called Alta. These guys aim their products at the existing dirt bike customer base. “That’s not stupid,” concedes Ytterborn. “It’s a wonderful way of serving that market with something that is electric, with all the benefits that come from that. But it’s not about optimizing the electric drivetrain in a backcountry environment.”

The second school starts with a traditional push-pedal mountain bike and outfits it with batteries and small electric motors. There are dozens of these small manufacturers around the world, from the Czech Republic and Slovakia to Australia and Holland.

Ytterborn chose neither school. Instead, he formed his own and enrolled immediately. While quick to give props to the likes of KTM’s Freeride and Alta for playing a critical, Tesla-like role in increasing market awareness and build quality for electric bikes, the people that inspired him most were the small-scale entrepreneurs, guys tooling around in their barns creating hybrid two-wheelers using a Frankenstein combination of bicycle and motorcycle parts.

If it hadn’t been for these garage-built hybrids,” Ytterborn says, “I would never have come to the conclusion of commercializing their initiatives. To adapt it where we have something that is seamless, more like an iPhone than a homemade telephone from 1975.”

Ytterborn doesn’t come across as a Deus-style motorcycle enthusiast, as one might expect from the head of a startup motorcycle company. Ytterborn approached the conceptualization, engineering, and execution of the Kalk not as a diehard rider, but as a veteran of gravity sports, road cycling and design.

It’s not like we’re pretentiously trying to think outside-the-box,” he tells me. “We simply come from somewhere else.” This independence led to an untethered imagining of what Cake could be—a blue-sky startup unrestricted by the motorcycle industry’s notoriously calcified thinking.

“I’ve been on electric motorbikes for the past three or four years, Ytterborn says. I bought them all just to understand what works and what doesn’t. And what we learned trying all these bikes was that it’s all about power-to-weight ratio, because the electric drivetrain behaves totally different from a combustion engine.” His conclusion? To optimize the off-road experience, Cake needed to start from scratch.

One of the biggest challenges was achieving precise throttle response. Consistent, immediate and smooth output required countless hours of testing, a year and a half of coding and recoding. In Christmas of 2016, Cake scrapped its work and started over.

Of course it’s wonderful to do big jumps, running through the woods at high speeds or whatever, but where an electric bike really amazes me is on tricky terrain. This spring, he was going uphill on a steep grade, over deep, wet moss. It occurred to him that if he’d been on a combustion bike he would have just ripped through it. But on an electric bike, you can go one mph, climbing really slow, and if there’s an obstacle you just think, ‘I need to get over it, I need more power,’ and it just gently takes you over it in perfect condition.”

And since the Kalk is electric, there is one gear and no clutch. (As most novice motorcyclists will testify, shifting on a bike is one of the trickiest processes to master.) The finished Kalk is a startlingly easy-to-use machine.

That potentially makes me happiest: It actually does what you think when you’re riding it.

What the Cake Is Made Of

By simply swapping out drivetrains like KTM, bikes end up weighing over 300 pounds. This is fine for MX or enduro applications, but for the back-trail exploring that Ytterborn sees as Cake’s bread and butter, the bikes are simply too heavy.

What you did today in the woods,” he says, referencing my afternoon lost in the Swedish wilderness, “flying on the trails, you’d never be able to do that on a 350-pound motorcycle.”

At the same time, outfitting a mountain bike with motors also has its issues. The most vexing one is that bicycle components are far too fragile for the increased stresses of electric motors. The solution? Build your own damn parts.

As Ytterborn’s son (and Cake social media director) Karl explains, “We realized that all of the most sturdy downhill bicycle parts were too weak, and all the motocross parts were too heavy, so we developed every single component from scratch.” Everything from stems to hubs is custom made, including an aluminum frame and swingarm, and carbon fiber body panels. When initially testing front suspension prototypes they realized stock 36-mm forks were too swampy and weak. So Cake collaborated with their fellow Swedes at Öhlins to build 38-mm forks exclusively for Cake—the precise size and strength for the duty at hand.

The wheels are built like highly reinforced downhill bicycle rims. This shaves 40 percent off the weight, but it also brings another helpful consequence: You can actually change a flat yourself. A struggle with traditional motorbikes is if you get a puncture in the woods, you better start walking. With a mountain bike wheel, simply bring a fresh tube and you can wrench it right there in the field. Cake developed an extra wide tire that uses 50% more rubber than a mountain bike to maximize the contact patch and designed a tread that avoids 90-degree angles, limiting environmental damage on the trails.

After experimenting with dirt and mountain bike handlebars setups, they settled on a custom-built unit using geometry closer to a mountain bike. “For test rides, we’ve used both experienced motocross and mountain bike riders,” says Karl. Over the course of these tests, they discovered a downhill bike-style stem that’s offset towards the front. “This makes the bike much more agile and nimble—it’s easier to throw around and you have more control.”

In the end, there are only three stock parts on the entire bike: brake levers, foot pegs, and rubber handles. That’s it.

What they’ve built is a vehicle imagined to be the ultimate exploration machine. It’s silent, so nobody knows you’re zooming through their woods; its tires don’t damage the ground, and there’s zero pollution. The Kalk is light (143 pounds), nimble, and easy to ride, and its 31-pound-feet of torque and top speed of 50 mph can get you out of (and into) any trouble, and the 50-mile range is just enough for serious trail riding.

Somehow, the Cake made me more confident, bolder. Before I knew it, I’m on the edge of a forest scratching my head wondering how the hell I got there.

A Designer’s Bike

Ytterborn wants to do to with Cake what he did with Ikea and POC: bring affordable style and aesthetics into serial production, to democratize design.

When the Kalk was first launched in January at Denver’s Outdoor Retailer Show, the bike was recognized as “Best in Show,” and sold out all if its 50 Launch Edition bikes in less than 3 weeks to 15 different countries. It went on to receive Teknikföretagen’s Grand Award of Design and Sweden’s national design award, the Design S. Recently it was nominated for a 2019 German Design Award, and this month was nominated for the Design Museum’s Beazley Designs of the Year award. Even if it doesn’t win, a Kalk will be on display at the celebrated London museum until January.

The innovation doesn’t end with the product. Cake commissioned pro enduro racer Robin Wallner to design a standardized 246-by-164-foot track optimized for its official category of ‘Light Electric Off-Road Motorbikes’. While motocross tracks are generally considered a noise nuisance, the silent, clean Kalk could run on a track next to a nursery school during naptime. You could theoretically build one of these tracks in the middle of Central Park, or by the Griffith Observatory. In the backcountry, an off-road motorcycle’s appeal is obvious, but the possibility of urban race parks cracks open a whole new market.

Cake has also been in talks with Formula E to build tracks that would fit in their city circuits for pre-races, as well as ski resorts to develop trail concepts. After all, Ytterborn sees the Kalk’s closest parallel as a downhill mountain bike, more so than an enduro racer. “It’s perfect on any trail,” he argues. “It’s like riding the fiercest downhill course on Whistler, but you don’t need a hill.” For surfers, skiers, skaters or anyone drawn to adrenaline sports, these light electric motorbikes could become a viable summer pursuit.

Given Ytterborn’s impetus has always been environmentally driven, he aligned Cake with Utellus, a Swedish renewable energy company, to develop three levels of solar panel packages to charge the bike for 100% zero emission cred

What It Costs

Cake designs and manufactures most of his own parts, and that comes with a price. The production version of the Kalk costs 13,000, which Ytterborn recognizes is high. The KTM Freeride E-XC, a comparable electric off-roader that comes with optional extra battery packs, is around 8,300 (extra batteries cost 5000,500 each). But Ytterborn doesn’t think of KTM as competition, preferring to compare the Kalk—loaded with aluminum alloy, carbon fiber, and levels of elaboration far beyond what the KTM has brought to market—to a top-tier mountain bike, which can easily run 12,000. For Ytterborn, the Kalk is to Cake as the Roadster was to Tesla—a proof-of-concept initially relying on early adopters. He is in no rush to ramp up sales, preaching deliberate patience in moving forward: in 2019 they hope to sell 300 bikes in North American and another 300 in Europe, roughly doubling that in 2020 until hitting a target of 5,000 bikes by 2022—at which time the Kalk will retail for around 8,500, or the same as the KTM.

“How you open the markets to Aspen, or Vail, or a wider market, you need to establish the credibility of promoting something that has true quality, that is among those who put the highest demands on products. That’s why we’re starting with a fairly expensive product without any compromises, to make sure that we have the perfect vessel that supports the intentions we have targeted.”

Soon a street-legal commuter version of the Kalk will debut with headlamps, blinkers, dashboard, etc., and what they dub a heavy motorbike in the future, loaded with ABS brakes and other requisite technology.

“But our intention is not to take market share from the motorbike market,” Ytterborn points out. “It’s about growing the motorcycle market. We’re not saying ‘Look at us: we’re better, we’re faster.’ We’re just different.”

We’re Really Doing This

On arrival, the Tennessee Trials Center offered well-kept and comfortable grounds. There was plenty of parking and space, even in the overflow section where we set up camp. Everything was within comfortable walking and/or riding distance. Making our way to the starting line to see what I had gotten myself into, there was a brief flood of concern. Can my bike do this? Can I actually do this?

At the start of the race, we lined up in groups of 5-6 bikes at a time. As soon as I was lined up, all of my previous concerns went away and I was in race mode. The air horn went off and we all began the race, starting with several log jumps before the fast and flowing grass track. This is my favorite kind of riding: I was in second through the grass track following a 20kW Sur Ron build. As soon as we entered the dry creek bed rock garden, the Sur Ron went down I and took the lead for my group. The hard enduro had just begun.

Now, I’ve ridden in rocks before. Missouri is known for its rocks. My usual riding area in Chadwick National Forest is full of them. This was different though, and I had never seen anything like it. My poor skid plate hadn’t either! This is what held me back the most. Although I wasn’t the slowest through this section, I wasn’t as fast as the Electric Motion trials bikes here. Thankfully, before long the rock garden ended (for the moment) and we were on to a more suitable tight single track which the Cake excelled in. By now my heart rate was through the roof and I mostly focused on breathing techniques, knowing this was, after all, an enduro: an endurance event.

| We’re a long way from Sweden. Photo by Roots Rocks and Mud

Good News and Bad News

Thankfully, I only lost one place in the rocks and quickly caught up to a couple more bikes in the single track. First was a new Sur Ron Storm Bee, which was unfortunately having a hard time on a steep hill climb. Next, I caught an Electric Motion E-Pure Race which struggled to keep speed in the very Endor-like single track. At this point, I was feeling pretty good and keeping a solid pace. that is, until I struck a large rock sticking out of a dirt berm, sending my chain off the sprocket. I immediately placed the chain on the top of the rear sprocket and rolled back down the hill, which to my delight worked! Upon taking off again, I noticed a terrible grinding sound but knew I had to keep going until either something broke or I finished the race.

Midway through the race, the Kalk’s motor started heating up. When this happens, the bike cuts back the power. This is either a fail-safe feature or a byproduct of the excess heat. Either way, it left me pushing the bike up a hill or two, but overall I was pleased with the bike’s performance, especially since there were overheated gas bikes scattered throughout the course all weekend. About that time, the chain hopped again. I stopped to check and it was on the outside of the chain guard which was bent in from the rock I had previously hit. I picked up another rock and hammered it back out. Thankfully, this solved the grinding noise, and I was off again.

In the next surprising turn of events, I approached a river crossing. Surely this wasn’t meant for electric bikes, I thought, but the race marshal signaled me over. There was only one way to go and it was through the depths of this river crossing. There was no turning back. I plunged my all-electric Cake Kalk into near waist-deep water, fearing that it would die while simultaneously feeling relief from cold water on my over-exhausted body. The bike not only made it through the water, but it also helped cool down the motor. With the cool-down, there was hope! Little did I know what lay ahead.

The Final Miles

The fast and flowing dirt was the Cake’s favorite kind of ride. It grips well, runs smoothly, and pulls like a dream. With a fully charged and healthy battery, it’s a fantastic ride. Unfortunately, the TKO terrain immediately brought back the amber dash light and decreased power of an overheated bike. To make matters worse, the sliding and spinning rear trials tire was taking a beating from climbing dirt hills without any grip. I couldn’t help but speak to my bike as if she were alive in a bit of delirium—begging the Cake to come to life and give me the power I desperately needed. Then another rock garden approached. This time It was even more difficult not having the extra power to help lift the front wheel over large obstacles. I was feeling mentally and physically exhausted, but I kept going all while praying I finished the race. I didn’t come this far to DNF.

The last rock bed of Tennessee boulders brought on a mental game of overcoming total physical exhaustion. The rear tire would free-spin as I lifted with what little strength I had left. I looked across the track and saw my wife signaling that the end was near. She shouted, “Don’t give up!” I needed this. Nearing the final stretch, the bike barely held enough juice to wind through the last section of the course. I carefully nursed the battery through each obstacle and barely rolled over the final jumps with an extra push. All four dash lights were blinking signaling that the battery was done. I had turned the mapping down to low power mode and cruised to the finish.

I made it. And all I could think was… well, I wasn’t thinking anything. I collapsed, throwing my helmet down to pour water directly on my head as the Earth spun around me. And the Cake? She would need several hours of charging, but what she lost in battery power, she gained in new-found respect from me. Having been surrounded by heavily modified e-bikes, I brought this mostly stock Swedish electric dirt bike on a journey that it was not designed for—a hard enduro—and we made it to the finish line of my very first Red Bull TKO with limbs and hardware intact.

| The aftermath: Torn seat and mud everywhere.

Damage Assessment

My Cake Kalk OR had indeed survived a proper hard enduro, but not unscathed. Because the OR’s large 80-tooth rear sprocket hangs so low, the chain had impacted multiple obstacles like rocks and downed trees. This ultimately damaged not only the rear sprocket and chain but, worse yet, the front motor countershaft stripped shortly after the race. On a traditional ICE bike this isn’t a huge hassle, but with the Kalk’s parts all being proprietary and Cake not having several parts in stock in the States, it’s turned into a waiting game. I reached out to Cake for support and was pleasantly surprised by the direct contact with a real person (Patrick) who seemed eager to help and was as excited as I was that the bike had made it through a hard enduro.

Seeing the other manufacturers at the event offering full support to the Electric Motion and Sur Ron riders made me hopeful Cake would eventually offer the same. As of now, I’m still waiting to see how racing a unique bike like this will work in the long run since when you race, things inevitably break, and downtime can make or break a race season when chasing points.

Dirt Kings: Rusty’s Race-Winning Segway X160 Full Moto Build

Rusty’s fully built Segway X160 has won races at E-Jam and beyond against much larger and more expensive machines. Come along for the ride as we interview Rusty about how his build came together.

| Cake on the ground, like a kid’s birthday party.

The Best Electric Dirt Bikes of 2023

Remarkably, only one of them went for the Dirt-E joke.

The motoring world is going electric. And it’s not just fancy, 1,000-horsepower, six-figure electric trucks. Electric motorcycle options have been increasing over the past few years. And even the relatively humble and underpowered dirt bike segment now offers a proliferation of emissions-free options — and we’re here to help you separate the battery-powered wheat from the chaff.

Why You Should Get an Electric Dirt Bike

Helps Save the Planet: Smaller motorcycles are far from the most fuel-thirsty vehicles. But electric dirt bikes still reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and every little bit helps.

America’s Toughest Enduro Race | Tennessee Knockout 2020 Recap

Less Maintenance: Electric motors require far fewer moving parts. That means more time riding and less time (and money) replacing parts. You also don’t need to buy things like oil.

Less Noise: Electric dirt bikes do make some noise, but they make less than internal-combustion dirt bikes — noise that can diminish the enjoyment of being in nature for riders and those nearby.

Accessible to New Riders: Like electric cars, electric dirt bikes do not need a manual transmission. This may disappoint some riders looking for a traditional feel. But it’s also way easier to manage while off-road.

Torque: Electric dirt bikes tend to have a lot of torque, and it comes on instantly. This helps them accelerate rapidly and feel quick in everyday riding.

What to Look For

Street Legality: Like combustion dirt bikes, many of them will not be street-legal. And you may live in a municipality that will confiscate and crush them if you try to use them for that — electric or not. There are dual-sport electric dirt bikes (lighter than adventure motorcycles), which can also be used as commuter bikes. But make sure you clarify that before buying.

Battery Range: Range is a significant drawback to any electric vehicle. You want to ensure you have enough range to do the amount of riding you’re planning. expensive electric dirt bikes will have range that can exceed what most drives can handle physically. But that may be costly.

Battery Charging: A nother important factor beyond range is how long it takes to charge the battery. Shorter is better. Manufacturers may offer accessories that improve charging speed. Some dirt bikes can instantly swap in a newly charged battery and return to the trail.

Canadian Rider Dominates Red Bull Tennessee Knockout

How We Tested

Gear Patrol writers and editors are continually testing the best electric dirt bikes on a variety of terrains to update this guide looking at features like comfort, ease of use and riding characteristics. Our testers have spent time riding the Zero XF and the Cake Kalk INK so far; however, we’ll be updating this guide as we continue to test more models.

Zero’s FX isn’t a one-trick pony; it’s good at a little bit of everything. It’s fast but torque-heavy up front. For comparison, it’s nimble but still about 50 pounds heavier than KTM’s 350EXC-F. And it’s quiet, which anyone who’s ridden a dual sport before knows has distinct advantages and downsides. (Upsides include not disturbing nature as you ride through and saving your eardrums; cons include being unable to announce yourself to other riders on the trail or cars on the street.)

The FX’s ride is very smooth — from city streets to rutted-out trails and even completely off-road in the ungroomed wild. The tires grip well on city streets, even after a light rain. The FX can reach a top speed of 85, but I rarely found myself pushing it above 65 — this is a great cruising bike built for the trails as much as it is for the road. The acceleration feels torque-y until you get the hang of the feeling; I’d recommend starting in Eco until you get a feel for how the bike handles, experienced rider or not.

The profile is lean and mean, just as advertised. Your tester is 5’4” and weigh 110 pounds, and she could handle and maneuver this bike with relative ease, although she did make sure to get comfortable on the bike on uncrowded trails before taking it to the streets. Zero says the charging time is 1.3 hours, but I found it to be much longer than that. the bike was delivered to me with an 80 percent charge, and it took more than two hours to get it full. The range is 91 miles which is a solid day’s ride, but unless you have the means to give the bike a good overnight charge, you’ll be SOL the next day. And that 91-mile range is in the city — if you’re riding on the highway at 70 mph without starting and stopping, it drops to 39 miles per charge.

We’ve been fans of Swedish manufacturer Cake — and Stefan Ytterborn’s helmet/eyewear/apparel brand, POC — for years. Founded in 2016, Cake has consistently put out smooth, innovative electric bikes that offer both gorgeous looks and purpose-built function.

The Kalk class of offroaders, however, is much more about play than work. The street-legal Kalk INK picks up quick thanks to 252Nm of electric torque, while reliable suspension (200mm of travel) and beefy dual-sport motorcycle tires help you keep the shiny side up from the road to the trails.

- Removable battery charges from 0 to 80 percent in two hours, 0 to 100 percent in three

- Three ride modes and three braking modes adapt to your style and environment

- Not exactly the cushiest seat on the planet (or this page)

- You must come to a full stop to adjust ride and braking modes